Valesuchi – Regreso (bc)

Sylvia Black – Hey You (sc)

Leonce & Girl Unit – “Thankful” (sc)

I revived an old music blog from the early 2000s?

Maybe it’s been a foolish endeavor, and maybe I’m the only one who misses the blog ol’ days, but I’ve been giving it a shot. I’ve been working on restoring some of the old content, though much of it was lost. I’ve slowly been rebuilding the old remix sunday archives, and even posting the occasional new edition. And I’ve been writing again.

You can find all the label’s releases here, on bandcamp, or most anywhere you listen to music these days. I’ve still got copies of some of the old vinyl releases, and I recently released the first in a set of charitable cassette compilations to raise awareness about the continued [mis]use of broken windows policing methods.

Plus, I put together a playlists section with a handful of spotify lists that hopefully start to capture a [slightly] updated version of the moods we used to peddle. Give those a listen and a ❤ if you would be so kind. If you want to get in touch, just give me a holler.

– Haldan/Boody

Valesuchi – Regreso (bc)

Sylvia Black – Hey You (sc)

Leonce & Girl Unit – “Thankful” (sc)

Princess Nokia – “Drop Dead Gorgeous” (sc)

Heems – “Rakhi” ft. Pavvan & Ajji (bc)

Zopelar – “Call It Love” ft. Hernbean5150 (bc)

Vegyn – “The Path Less Travelled” (bc)

Loukeman – “Won’t U” (bc)

Soho Rezanejad – “L.O.V.E” (bc)

On the one hand, this is inspiring. But on the other hand, it’s scary. It might be for the best.

How does one trace the line between jubilation and heartbreak? How can it be possible that opposite poles so often sit so close to one another? Maybe most spectrums are simply not linear; circularity is probably a better form on which to picture them. The furthest measurable distance on this kind of scale may not be between joy and misery, but rather between extreme and stable.

Qoryqpa (Streets Loud with Echoes) is a film by Kazakhstani filmmaker Katerina Suvorova that follows members of grassroots activist organizations in Almaty for approximately five years. It takes place largely in the immediate aftermath of the death of Denis Ten, a national icon and figure skater who was killed by carjackers attempting to steal his side mirrors. It traces the political movement that arose following his death, leading to the resignation of the country’s first president—who ruled the country for 30 years, and whose tenure began before the fall of the Soviet Union—up until the violent unrest of January 2022 that led to the deaths of over 200 people. Despite the intensity and passion with which many of the activists tracked in the film hold their beliefs—and the brutality and violence with which some are met—possibly the film’s most striking quality is how elegantly it demonstrates Hannah Arendt’s concept of the banality of evil. Everyone in the film, including the activists, police, and judges, are all purely human; these are ordinary people on either side of the fight for constitutional reform, all victims of extreme oligarchy regardless of their political posture. Despite being similar in most respects, they sit at opposite political poles of a circular spectrum, their backs almost touching.

A similar paradox exists for the protest movement itself. This doesn’t initially look like a radical movement; it’s one led by precocious innocents gently using their voices in an atmosphere so used to quiet that even a whisper in protest is viewed as disruptive. And the suppression is comparably benign at first, mostly enacted by visibly confused civil servants. The activists at numerous points in the film also seem to express caution with the whole endeavor. There’s a shared understanding that even if all this could lead to the sort of political upheaval they seek, for the right reasons and by righteous people, there’s the distinct danger of co-optation by darker political forces waiting in the wings. Revolution by the good against the bad can upset the familiar equilibrium enough to lead people to accept rule by the worse. Nonetheless, the film’s central message is that these are risks worth taking, that fear of speaking out is the ultimate enemy here and sacrificing the stability of poor governance is just a stop on the way toward liberation. It’s a hopeful film, but one that both begins and ends in a liminal space. Kazakhstan is still a country with very little space for opposition, minimal freedom of press, and only a semblance of opportunity for substantive political participation.

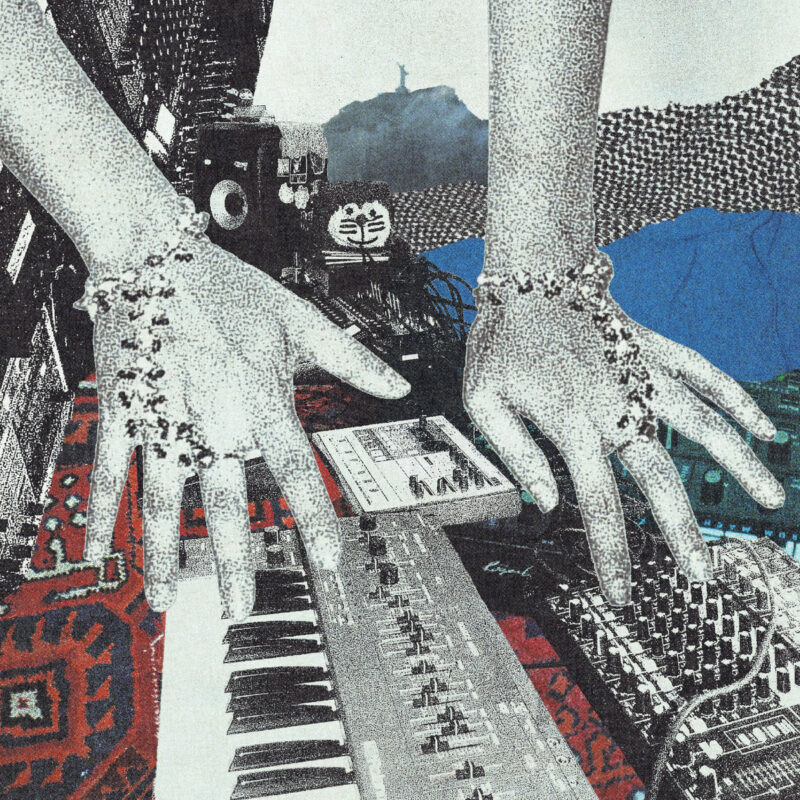

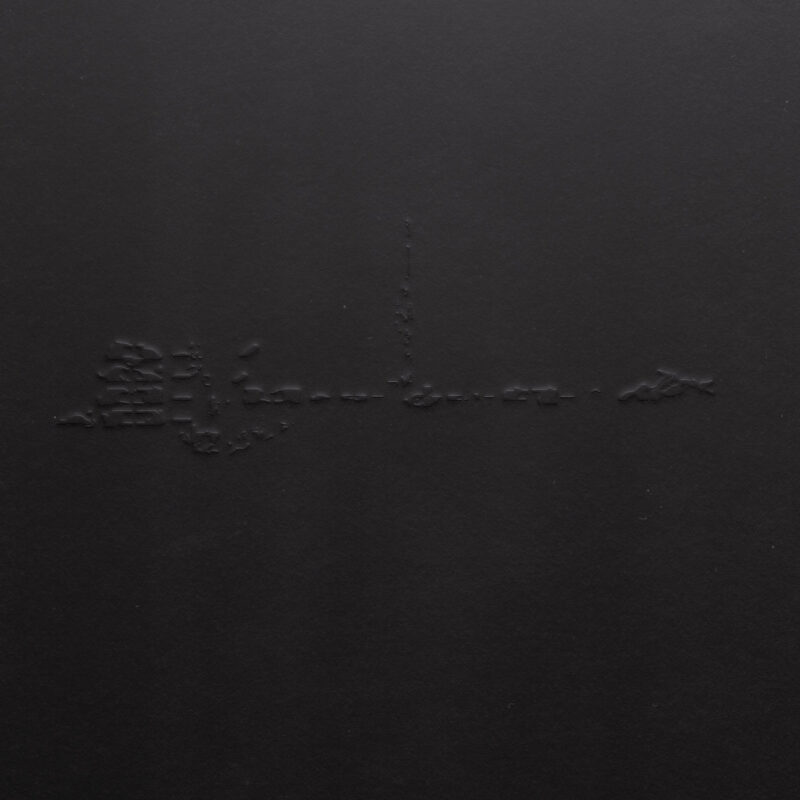

Gently tracing the lines around the film’s cautious optimism is an exceptional score by Tommy Simpson, aka Macro/micro, whose work I’ve written about consistently over the past few years. I probably say this each time I write about him, but this is without doubt the best record he’s yet delivered. It reinforces the tone of the film: the dreary tension of “Balaclava” is built upon the rhythmic repetitions of a windshield wiper, and seems to reflect the precarity of the activists’ choices; the dissonant clatter of “Indiscriminate” elicits the fear and ferocity felt by protesters (and passersby) at the hands of the police’s violent repression. But most of all, the record feels like a love letter to Almaty and Kazakhstan more generally. This is fitting; Simpson shared with me that he traveled to Almaty in 2014 with a friend, fell in love with a woman who asked him to DJ the opening of her flower shop, got married and stayed there until late 2018, at which point he and his wife returned to Los Angeles together. Songs like “Oyan,” “Qazaqstan,” and “Tengri,” are beautifully tender and admiring—clearly the work of someone in love with this place and its people. The album’s closer, “Almaty,” is the most hopeful of all. It’s anchored by the sonogram of Suvorova’s unborn child’s heartbeat, who is revealed at the end of the film as the object of her narration, and in light of whom she reframes the liberation movement itself. It’s no wonder she can be hopeful in the face of continued repression and uncertainty. What wouldn’t we do to ensure our children don’t have anything to fear?

Qoryqpa has not yet seen wide release, but is on the festival circuit and will hopefully be more broadly distributed soon. Simpson’s score is out now for streaming all over, and can be purchased on bandcamp.

Macro/micro (Tommy Simpson) – Streets Loud with Echoes (Original Score)

After a long summer vacation, I returned to this record in my inbox, sent over by an artist named To the Tide, who also makes music as Silk Static, based in Vancouver, BC. According to the artist, Sleepless Sunrise is meant to reflect those sweet mornings after a night too exciting to consciously close. Seeing the sun rise on those mornings is probably among the last swells in a series of heart gushing or positively delirious moments. It might have been the euphoria of the rave; or that intuitive bond between friends that bordered on the telepathic, keeping them rapt all night long; or just the buzz and unstoppable flutter of a new crush. But the dawn comes nonetheless, bittersweet as it might be.

Sleepless Sunrise is without doubt a romantic record, from the deeply tender and brittle closer “Flourish,” which is my favorite of the six, to the lumbering optimism of “Cathartic Koto” and traipsing serenity of “Thoughts Unclouded.” But as much as this may be a record primarily concerned with capturing the warmheartedness of a morning following a night of human connection, it could probably equally serve as a comfort for those who’ve been up all night for the opposite reasons. It could be a gentle reminder that even those hypomanic lonely nights anxiously flitting from one distraction to another can end in a nourishing cleanse of light and quiet.

Sleepless Sunrise is out now on bandcamp, or for streaming.

To the Tide – “Flourish” (sc)

Not everyone

is a physician

but sooner or later everyone

fails to heal.

In Gaza, a girl and her brother

rescued their fish

from the rubble of airstrikes. A miracle

its tiny bowl

didn’t shatter.

– Fady Joudah

Remix Sunday 169 Zipped Up. (105mb zip)

Marina Herlop (MC Johny Oliver x Cirilo) – “Miu” (DJ Lukinhas ‘MTG Assombra Pitchfork’ Bootleg)

James Blake – “He’s Been Wonderful” (DJ Carlozs & DJ Dimas ‘A Moda Do Verao’ Mix)

MC Denny – “A Mamada Quando é Boa” (Crosstalk Dub)

Destra – “Dip and Ride” (Rizzla Bootleg)

Luniz – “I Got 5 On It” (Thys ‘Puff On It’ Bootleg)

Willa Ford – “Did Ya Understand That” (Cameo Blush Bootleg)

ENiGMA DUBZ – “We Can Go” (Mystic State Remix)

Kerri Chandler & Jerome Sydenham – “System” (Helix Remix)

Boards Of Canada – “Amo Bishop Roden” (GAZZI Break Mix)

Charli XCX – “Everything is Romantic” (Loraine James ‘everything is romantic on a gr-1’ Remix)

image/ Justine Frischmann

Wiki – “No L’s” (prod. Tony Seltzer & Jam City) (sc)

Lol K – “Outside Chance” (bc)

First up today is this pair of strong submissions from Her Waveform, an artist from Naarm (Melbourne), Australia. Both of these are from an upcoming album, due later this year, all of which is built largely from improvised stereo track recordings with no editing after the fact. The first is a cut of gritty propulsive abstract modular techno, where the second tends towards the dreamy and transcendent side of midtempo broken beat and glitch hop. You can grab both of these on bandcamp or stream them wherever you tend to do that sort of thing.

Her Waveform – “Study” (sc)

Her Waveform – “Plictisit” (bc)

![]()

Next up is a heavenly bit of melancholy throwback euro-dance-pop. A collaboration between Danish artist The Bird (real name Yunus Rosenzweig) and True Blue (Maya Laner), whose earworm single “No Water” became a surprise rinse of mine a few years ago. Notably, Rosenzweig appears to have collaborated with a who’s who of the Danish pop-arthouse scene, and Laner is currently a member of Caroline Polachek’s excellent live band. No bandcamp for this unfortunately, but you can find it on all the streamers, and the artists have generously allowed me to share with you the mp3.

True Blue & The Bird – “Truest of Blues” (mp3)

True Blue – “No Water” (sc)

![]()

Last but not least is this energetic roller from Dutch producer not yes, a nod to the ravier side of US breaks. I don’t know anything else about not yes, but this track is a straightforward and effective dancefloor tool, so I can definitely recommend it. You can grab this on bandcamp or for streaming, but not yes has generously provided the mp3 for all the DJs out there interested in taking this for a spin.

not yes – “switchblade knife shit” (mp3)

Mount Kimbie – “Shipwreck” (sc)

Armand Hammer – “Doves” ft. Benjamin Booker (sc)

Wu-Lu – “Daylight Song” (sc)

Brassica – “Turdnadoe” (sc) [buy on bc]

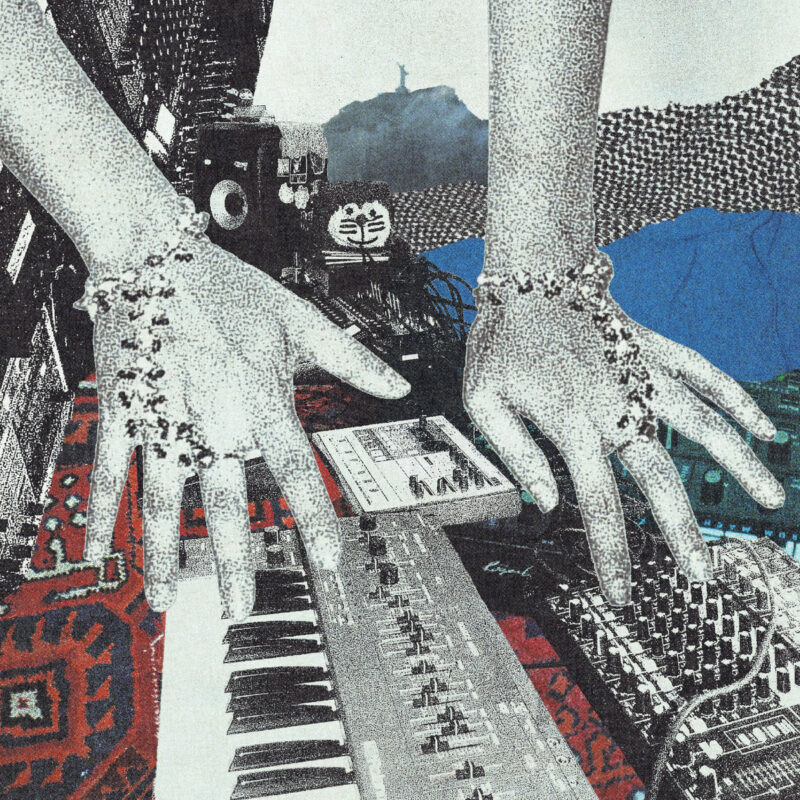

Sully & Salo – “Nights” (Not Just A Dub Mix) (sc) [buy on bc]

Lanark Artefax – “Meszthread” (sc) [buy on bc]

First up this week is a patient and intricate cut of dubby electronica from Lansing, Michigan-based bioPrism, real name Josh Epperly. Implied perhaps by his pseudonym, Epperly is a biologist—specifically an ecologist—whose research has focused on the study of river insect communities. His fascination with the natural world has informed his music, with the aim of reflecting the complexity of living systems through sound design. You can grab this on bandcamp as part of the Anthropocene EP or via the typical streamers, but Epperly has also generously allowed me to share an mp3 with you all here.

bioPrism – “Neon Mirage” (mp3)

![]()

Next up is this vibrant, playful, exploration of 9/8 polymeters from Toronto-based producer Katret. This embodies for me the inclination to jump two feet first into a puddle in the middle of a summer rainstorm; irrepressible exuberance in defiance of one’s surroundings. This is unfortunately not on bandcamp, but you can find it on all the typical streaming outlets.

Katret – “Kat Tracker” (sc)

![]()

Last up today is a track from Aaron Horn, the second offering from his upcoming debut LP All the Love Within. I’ve written about Horn a couple of times before, including posting the first single from the LP, and some of his work as part of the Grammy Nominated due Crate Classics. This one centers around a contemplative looping vocal refrain, and is underpinned by a simple and effective combination of midtempo dembow drums and a gently meandering bass line. No bandcamp, but Horn has kindly offered up the mp3 for you all here. The song is also available on all the streamers.

Aaron Horn – “In Your Arms Again” (mp3)

Thomas Bangalter – “CHIROPTERA” (sc)

Multiform Palace – “Tompkins 88” (sc)

Slim Soledad & Iki Yos – “T.E.T.A Intergalactica” (sc)

More fire from Ottawan stalwart So Durand, who I’ve been following closely the last few years. I’ve covered him a few times, but this is definitely my favorite release from him thus far. 2-step ragga meets revivalist heavy bass. That kick drum also just has a perfect woody stomp. And keep an ear out for some classic loon calls. Out now on bandcamp and for streaming.

So Durand – “Révolte” (bc)

![]()

Next up is this near-perfect tune from Danish-Argentinian producer and pianist, CAPITANA, real name Nanna Fittipaldi Giobbi. Giobbi’s music is meant to reflect themes of rootlessness, as someone whose sense of social identity is divided between Scandinavia and Latin America. I can definitely identify with this notion, as a half-Dane, half-American whose life has been spent grappling with the questions of where my roots run deepest, and where to put down new ones. I may be reading into the music too literally here, but I definitely hear that rootless quality in Giobbi’s music, particularly in the airy untethered quality of her piano melodies. CAPITANA has had some heavy co-signs, having contributed piano to a King Krule record a few years ago, and recently garnering the support of the likes of Erica De Casier. No bandcamp for this, but Giobbi has been generous enough to let me share with you the mp3. It’s also available all over for streaming.

CAPITANA – “Real” (mp3)

![]()

Last up is this lovely cut of lofi house from Belgrade-based producer Scasca. This is like duvet music. True to its title, it’s delicate and warm, with no harsh edges, just comfort. I don’t know much about Scasca, but they’re current with an EP called Spring Station, of which this is one third. It’s out now on bandcamp or for streaming.

Scasca – “Give Me Just a Little Warmth” (sc)

As horrifying and destabilizing as the pandemic was, time seems to evince that it also presented an opportunity for many to explore sides of themselves they previously had been unable to. The clichéd examples of this were the surge of new sourdough bakers, home improvement mavens, and amigurumi makers—the effects of all of which are still evident all over social media, farmers’ markets, and swap meets. Aside from those, however, as I’ve been reviewing blog submissions over these past few years, a story I keep hearing is how many musicians in bands took lockdown as an opportunity to start making music alone; and naturally, electronic music lends itself to working alone.

One such musician is Glance, an Irish-born artist living in Amsterdam. After years as a drummer in the Irish hardcore punk and metal scene, the lockdown allowed (forced) the time and mental space to pursue a long-held curiosity about electronic music production, particularly using modular gear and other hardware. Given their background as a drummer, the music that has resulted—the Temple EP—is thoroughly and pleasantly drum focused. Each of Temple‘s four tracks relies heavily on sequenced breakbeats — and with BPMs from 155 to 175, it’s all in the jungle and D&B universe. All the ingredients are there for an easy win-me-over: sharp, liberal use of open breaks; recondite vocal samples; a nice balance of glittery arpeggios and pads against repurposed jazz samples. The winner for me is definitely the EP’s closer “Cavalry” which trades all the reese and reverse bass for an almost-unnerving combination of subbass rumble and contrabass that underpins a tortured time stretched horn line and a disembodied voice that tells us “the kids are changing, and so has the music.” From the quality of this record, you’d never really suspect Glance is new to making this kind of music. The kids might be changing, and so might the music, but records like this demonstrate a course change can lead to welcome outcomes.

Temple is out now on bandcamp, or for streaming.

Glance – “Cavalry” (sc)

Glance – “Temple” (sc)

Lush glitch and bass from Los Angeles producer Iris Ipsum, real name Sol Rosenthal. This is meticulously produced and sharp stuff, but with enough round-around-the-edges to keep it pleasant enough for a sunny day. Properly LA forward-thinking electronic music. If you’re intrigued by the production techniques on this, I also suggest you check out Rosenthal’s gumroad, which has a slew of really exciting M4L patches available for free (or whatever you wish to donate). “Subspace” is out now on bandcamp as part of the Xtilde EP; it’s also available for streaming wherever.

Iris Ipsum – “Subspace” (sc)

![]()

Another artist from LA, next up is a punchy cut from Lake Hills that sits somewhere between electro and US breaks. Plenty of waggle to this one, shimmery overtones, and a nice murky vocal undertone. All that works for me. When I heard this at first, I could sense Lake Hills was probably fond of Elektron gear; I then stumbled across this fun live in-studio session he did with edIT a few months ago, which confirmed that suspicion. Hard not to love those Swedish rytm boxes. This is out now for streaming anywhere and everywhere.

Lake Hills – “Picking Flowers” (sc)

![]()

Finally, a shift back to my side of the country with some sweet vocal electronica from Indian-born and New York-based producer and vocalist, tanvi everywhere. Inspired by a long-distance relationship, this mines the infinite well that is longing and dull heartache. No shade, it’s always effective subject matter because we’ve all pined for someone, whether separated geographically or otherwise. This is out now for streaming all over. No bandcamp, I’m afraid, but thankfully tanvi and her label have been kind enough to let me share the mp3 with you below.

tanvi everywhere – “Need You Now” (mp3)

Tul Waitoonkiat – “Nueng Kamtham” (Black Merlin Traverse Dub Mix) (bc)

404 Shadow – “Turn the Page” (sc)

Another soaring beauty from Sound of Fractures, aka Jamie Reddington, who I’ve covered a number of times here. Reddington’s music is much like what he reflects on socials: open, sincere, and willing to embrace the flush of emotions that comes from being a father. This is the next to final single from his interactive Scenes project, for which the final single is currently accepting submissions. Head over here to participate.

Sound of Fractures – “Meant To Be” (bc)

![]()

Next up is an touching slice of leftfield/glitch hop from Australian BKLV. Lovely sludgy stuff here, with moments of pure melancholia. Fitting, as the song was written in memory of the artist’s cat and studio buddy (listen for the audible purring). I recently spent a huge part of my savings to rescue my cat from near-certain death, so I can definitely empathize with how important and deserving of honor our feline friends are. This is out now for streaming, but you can also grab it as a free download below, thanks to the artist’s generosity.

BKLV – “Boundless” (mp3)

![]()

Last but not least is this excellent bit of club fusion from St. Louis’s Umami (aka Pajmon Porshahidy). At the encouragement of Palms Out stalwart, Bianca Oblivion, Umami merged elements reflective of their Persian heritage with breakbeat, bass, and jersey club. Straightforward and effective dancefloor material here, I expect this would hit perfectly for the right audience. This is out now for streaming, but Porshahidy has also kindly provided the mp3 for all the DJs out there eager to test this out for themselves.

Umami – “Djadou” (mp3)

There’s a common perception of modular synthesis (especially Eurorack) as only suitable for either (a) long-form generative ambient music, or (b) noodley glitch and noise. Another common opinion of modular—or at least of the musicians who invest in it—is that it’s primarily an exercise in vanity, or just a pure expression of gear acquisition syndrome. I’ve had these doubts about my own forays into modular, especially when I’ve considered how much strain it can put on my pocketbook. There’s definitely some truth to all of these clichés; plenty of people with big Eurorack setups let them collect dust, or at least only use them to fiddle around, creating ephemeral soundscapes with little utility for music they actually release to the public (if they release any music at all). Nonetheless, these are not necessarily pointless pursuits—sound for sound’s sake is perfectly reasonable as a goal in and of itself; and I don’t even fault a pure collector. I’ve collected ephemera of various sorts my whole life, and I have found lots of satisfaction in doing so.

But none of this is the only way to use modular. The wonderful thing about it is that it can be whatever you make of it. Its power is in its flexibility. Music For Modular is the latest album by London artist Lazy H, and is a brilliant example of modular’s versatility. While there’s plenty of exciting synthesis and sound design at work on this record, it’s also a demonstration of how a modular setup can integrate comfortably into a classic band format, playing a role alongside live drums, bass, and keys. Most importantly, Music For Modular is distinctly musical. It has its atmospheric moments (opener and closer “Start from an Arp” and “Allen” fit this bill), but it’s far more an exploration of the danceable and melodious sides of jazz and funk (lead single “Body Thaw” and “Quicksilver” as the best examples). My pick from the record is “Tadasana Pose,” which oscillates between viscous, syrupy glitch hop and total serenity—with stretches that seem to even approximate prayer music.

None of these genre-descriptors are particularly useful here, though, and may end up reductive. What’s evident throughout the album is that this is music that emerged from spontaneity. It’s not the robotic navel-gazing of a lone synthesist. Instead, it’s the product of improvisations that have let the synths act as warm and expressive instruments with as much personality and elasticity as any physical instrument. This may be music for modular, but it’s music by humans.

Music For Modular is out now on bandcamp or for streaming.

Like so many others, in the few years preceding the pandemic, I sheepishly fell for the lofi girl. It was truly easy listening for millennials (and zoomers). At the time, I was overwhelmed with studying for the bar, so when I wasn’t actively writing music myself as an outlet for the stress, I simply could only handle background music. I was exactly the demographic the chilled cow was targeting, someone who only needed music to study to. But despite generally not paying close attention, I would occasionally notice a song here or there that would stand out from the rest, and make note of the artist. It often struck me how many of them seemed to be producing these lofi beats in parallel to other styles, sometimes many other styles. It was as if, for many of these artists, the production of the study beats served a similar purpose as did the listening: reducing stress by embracing the loopy calm. Often a quick dig into these artists’ catalog would reveal they primarily produced brostep or house or metal, or all of the above, or just whatever. There was seemingly no unifying route to the study beats, just a collective individual embrace of the microgenre youtube birthed.

I was recently sent this lovely record by Scranton, PA-based producer, Broey. His latest record is Fragments, a nice and sweet 24-minute journey through an array of midtempo house subgenres. As it turns out, Broey. is exactly one of these types—a guy who’s been making music for years, and who’s explored a range of genres, but who’s seen the most substantial reaction to his contributions to the world of study beats. He himself describes those contributions primarily as community efforts—lots of collaborations, and a way to connect with like-minded producers across the globe. This in contrast to Fragments, which he describes as a passion project.

Fragments shines in the moments when it focuses more on the fundamentals. The stand-out is without doubt the opener, “Like That,” an effective and pleasingly modern take on Chicago house, even flirting with elements of juke. Similarly, “Run For Cover” is my second pick because it doesn’t try too hard to get fancy. It’s bread and butter modern house music primarily suited for a dancefloor, but with enough hookiness and personality to stick in your ears after the fact. You can tell Broey. is a producer who can shape-shift, and that’s enviable, but it also seems like with this project he’s intent on drilling down closer into the music he actually loves. Study beats are a means for many to maintain equilibrium and even make friends, but underlying all those waves and waves of constant chill, we all need some substance.

No bandcamp for this, unfortunately, but you can find Fragments for streaming all over.

Broey. – “Like That” (sc)

Broey. – “Run for Cover” (sc)

I’ve posted about Mattr (aka Matthew Clugston) a few times, and I like each track he puts out more than the last. This is one is no different. Intricate and elegant electronica; all whispers, gauze, and pearls. This is from his forthcoming album, due out May 31st. It’s out now on bandcamp and for streaming, but Clugston has kindly offered it for free download below.

Mattr – “Cholia” (mp3)

![]()

More exquisitely delicate electronica, this time from San Diego-based Blaine Counter, aka Graffick. I’ve previously posted a couple of his other singles, which were both propulsive and drummy affairs. He’s back now with something more contemplative, a lush nighttime hike up Cuyamaca Peak. Heavenly stuff. From his upcoming LP, Spectra, out later this year. No bandcamp for this, but you can find it streaming, and Counter has generously allowed me to share the mp3 with you below.

Graffick – “Messages / In the Wake” (mp3)

![]()

In a nod to their heritage, Hanover-based duo pølaroit recorded a massive organ in a local church, holding chords and simultaneously pulling the organ stops, gradually filling its pipes with air until the organ’s sound had swelled immense. These recordings were incorporated into this nice bit of warm and gentle piano-driven house. No bandcamp for this unfortunately, but you can catch it on any of the streamers.

pølaroit – “The Organ, Pt. 1” (sc)

Ivohé – “yemmal2am” (mp3)

ALIAS – “COCKTAILS AND DREAMS” (sc)

Kamasi Washington – “Dream State” (ft. André 3000) (bc)

كيف يمكن ألا يستطيع الإنسان أن يسير إلى ملكه الخاص؟ أن يزور قبر زوجته؟ أن يأكل ثمار أربعين جيلاً من كدح أسلافه من دون أن يعاقب بالموت رمياً بالرصاص؟ على نحو ما، لم يكن هذا السؤال الفجّ القاسي قد نفذ سابقاً إلي وعي اللاجئين الذين شوشتهم أبدية الانتظار، معلقين آمالهم على قرارات دولية نظرية

How can a man not walk to his own property? To visit his wife’s grave? To eat the fruits of forty generations of the toil of his ancestors without being punished by death by firing squad? Somehow, this harsh, harsh question had not previously penetrated the consciousness of the refugees who were confused by an eternity of waiting, pinning their hopes on theoretical international resolutions.

– Susan Abulhawa, Mornings in Jenin

Remix Sunday 168 Zipped Up. (99mb zip)

Omar Souleyman – “Nahy” (مُخْتار moktar edit)

Sango – “Me dê Amor” (Ballads Edit)

Aysha – “Baddie” (Crosstalk Remix)

Charli XCX – “Hot In It” (QRTR ‘Madame’ Flip)

Men I Trust – “Sugar” (Tom VR Edit)

Alex Iso – “Fifth Kiss” (Alpha Delta Remix)

An Avrin – “Snake” (BABii dub)

Frank Ocean – “Chanel” (camoufly Remix)

Cherrelle – “Saturday Love” (Wilhelmina Bootleg)

Jill Scott – “He Loves Me (Lyzel in E Flat)” (CalvoMusic Edit)

image/ Massimo Vitali

It’s a touch comical how much I’ve written about Boards of Canada on this blog over the years. In 2021, I wrote a piece about the Kahvi Collective’s Tangents compilation, which was an unrepentant Boards of Canada tribute album, made out of a longing and impatience for more BoC material. On that record, we heard manifest the yearnings of fifteen artists expressing their devotion to the Scottish duo. At the time, I wrote about the compilation as if those songs were made specifically in tribute, almost as an invocation for the brothers Eoin/Sandison to return from their hibernation. While it may partly have been that, it may have been naive of me to think those artists weren’t already writing music like that out of pure inspiration, not just as an exercise in conjuration. BoC are not just missed, they’ve also legitimately birthed a subgenre.

It’s no longer enough to recognize that BoC’s music revolves around nostalgia; their music has become nostalgia. A generation of musicians like me have grown up with them, and now many of their qualities have been absorbed and become the sincere expressions of others. It’s almost unfair to call the resulting music derivative, or at least not in a critical sense. It’s like calling Raider Klan records derivative of Three Six Mafia; or modern electro released on the likes of Central Processing Unit derivative of Planet Rock, Kraftwerk, or Cybotron; or the sea of current ambient music derivative of Brian Eno. Sure, in all these examples, the current artists working in those subgenres do literally derive portions of their sounds from the work of those originators, but participating in a subgenre doesn’t make one’s music unoriginal, or for that matter any less enjoyable or emotionally important.

Parable (real name Julien Hauspie) is an artist from Kortrijk, Belgium. He belongs to this generation of consanguineous artists, linked by their mutual debt to Eoin and Sandison. His debut album is Monument, self-released earlier this year. While it certainly owes much of its sound to the oft-mentioned duo—particularly in its pace and liberal use of reel to reel tape warble—Monument is gorgeous in its own right. Perhaps more importantly, I walk away from it firmly facing forward, filled more with hope than a romantic aching for the past. There’s something matutinal about this record; it’s a sunrise record. It’s open-hearted and full of light and warmth. BoC records are of course some of the warmest electronic music ever produced, but they are often sunset records, characterized by a contemplative rear gaze, as opposed to an eagerness to tackle whatever today has in store.

Hauspie apparently wrote much of the record as an ode to the nature he experienced while backpacking across Europe, which may explain some of Monument‘s wide-eyed optimism. Even the record’s darker moments (e.g., “North Central”, “Undercurrent”) can’t quite contain the underlying flashes of light; the hope overpowers the melancholy. There are dozens of quietly joyous moments throughout the album, but Hauspie’s compositions shine brightest when he lets down the guardrails and embraces the ecstatic. The album’s opener, “Taking Control” brims electric; “Flashpoint” is like a modern day pagan devotional, rich with a sense of gratitude for the natural world; and pre-release single “Pin Drops” stirs in me the desire to run wide-armed through a wheat field. (By the way, I posted the lovely video for “Pin Drops” a few months ago, which is well worth checking out.)

Ultimately, Monument is a record beaming with love and sincerity. There’s enough of the past in it to make me smile about what I’ve already loved, but more so, it makes me want to bring new into the world.

Celestial dembow from 1tbsp (real name Maxwell Byrne aka Golden Vessel). This has that satisfying balance of serenity and energy that would make it great for rolling (or just dancing) on a beach as dusk sets in. This is from 1tbsp’s upcoming Megacity1000 album, and is available now on bandcamp and for streaming; but he’s also kindly allowed me share with you the mp3 below.

1tbsp – “Starchitect” (mp3)

![]()

Next up is this bouncy hi-NRG UKG number from Danish producer SAGE D. (apparently a new pseudonym, but not sure what the old one was). Love the distortion level on the percussion here—flirting with the edge of over-distortion can really add extra life to a song. No bandcamp here, but available for streaming. Grab the mp3 below (or head to soundcloud if you’d like the WAV). There are a bunch of other strong tracks there for free download.

SAGE D. – “THE WAY U FEEL” (mp3)

![]()

Last up, but definitely not least, is this sublime track from Aaron Horn, whose Crate Classics project I posted about a couple of weeks ago. From his upcoming album All the Love Within, this is somewhere between footwork and jungle, but in the gentlest of ways, all anchored by a Horn’s delicate vocal refrain. No bandcamp for this, but Horn generously provided the mp3 below, and you can also catch this for streaming.

Aaron Horn – “UPWRDS” (mp3)

MOY – “Frequency of Creation” (bc)

Tati au Miel – “My heart” ft. Cecilia (bc)

Erika de Casier – “Ex-Girlfriend” ft. Shygirl (bc)

Sugary, airy jungle/liquid from Sydney duo Possible People (producers Pinz and Tulett). This is my kind of easy listening, I could listen to this sort of thing in the foreground or background all day long. This is part of Possible People’s upcoming sophomore release Drop In, out on April 26th on Sydney label Extra Spicy, but in the meantime the artist have given me permission to share the mp3 below. Preorder the record on bandcamp or find it for streaming once it’s out.

Possible People – “Fall in 2” (mp3)

![]()

Sharp left turn now to this gnarled, humid, sex anthem for club goblins, from LA’s Tony Pops. This is all sweat, sex, and leather. There’s even an interpolation of the “Thong Song” in there, which can almost never be a bad thing. No bandcamp for this, but Tony has been generous enough to let me share the mp3 below. You can also find it for streaming all over.

Tony Pops – “Playa” (mp3)

![]()

Last but not least is yet another top-notch track from Big Dope P, who rarely delivers anything I dislike. I’ve covered a couple of the other prerelease singles for his upcoming sophomore album Toto La Castagne, but this might be my favorite so far. Low-key by Doppie’s standards, and featuring vocals from Spanish artist BFlecha, it sounds like a mellow late-80s freestyle B-side for wooing the uptown girls. Few compliments could be greater coming from me. Preorder the album on bandcamp and get this and the other prerelease singles right away. The album’s out May 10th.

Big Dope P – “Event Horizon” ft. BFlecha (sc)

In 2015, I worked briefly as a project manager at a record label in Brooklyn that primarily released Jamaican dancehall and dancehall-adjacent music. As a result, it wasn’t uncommon to see deejays (in dancehall terms, that means a vocalist) come by the office to voice riddims the label was pushing, or otherwise make use of the label’s fancy studio. Toward the end of the summer that year, one of my bosses called me one morning and told me in a somewhat hushed tone that Lee Perry was going to come by to work on some music. The tone was called for. After all, the man was a living legend, having led the Upsetters, produced and released early Bob Marley and Max Romeo records, and collaborated with everyone from The Clash to Paul McCartney. For my own sake, I revered Perry mostly because of his role in pioneering dub music and its associated production techniques, in parallel with the likes of King Tubby and Scientist. I love old dub terribly, but I also credit those techniques as the seed for many of the subsequent genres that I hold dearest.

The label’s owner, who largely owed his career to the work of pioneers like Perry, was understandably deeply excited. He even had a set of action figures depicting Jamaican musical icons that decorated a shelf in the studio’s control room; a Lee Perry among them. The rest of us were a little tense too, not only because of Perry’s legendary status, but also because he had a reputation for being a madman. He had claimed to lead an alien race living on earth, and he was rumored to pour blood on his equipment and master tapes in order to preserve them. When he arrived, he was generally subdued but friendly enough. I didn’t get to sit in on much of the session, and had to run the office while my bosses got to go have fun, but from what I did observe, his imagination was as vivid as ever and his eyes wide.

As far as I know, nothing came of the recordings made that day, but after he left, his action figure was mysteriously gone too. (He eventually mailed it back from his home in the Swiss Alps.) Like those unused recordings, I’m sure there are literal hours of Perry’s music that remain unreleased. Though he died in 2021, music has continued to pour out, with dozens of posthumous releases already. This song is among the latest. I don’t know much about it or who’s behind it—it’s released on a label with very little digital footprint, MoSai Music. As far as I can tell, the label has only released music from one other artist, an album called Paris Mosel by Skinny Pablo, about whom I know nothing, but the album is dope. While it’s possible Perry produced this song himself, it’s unlikely, since most of his output in the past decade has been produced primarily by others, with him instead serving the role of deejay. Given the sound of this song versus that of the Skinny Pablo record, it stands to reason that Skinny Pablo may have had a hand in producing this, but maybe not—time might reveal the details. In any case, this is my kind of Perry record: hypnotic and dubby; an exaltation of, and incantation to, the aliens.

This isn’t on bandcamp, unfortunately, but it’s available for streaming, and thankfully the publishing company behind it has kindly granted me permission to post the mp3 here.

Lee “Scratch” Perry – “Real Love” (mp3)

Scandinavian/Baltic theme to today’s roundup post. First up is this piece from Helsinki-based Jonas Verwijnen from his debut EP1. The record is a personal one, and an attempt to navigate the complexities of human interaction as someone living with autism spectrum disorder. Really beautiful stuff. No bandcamp for this, but it’s available for streaming all over.

Jonas Verwijnen – “This Is Going Down The Wrong Path” (sc)

![]()

Next up is a striking cut of broken techno from Seal Pup, about whom I know next to nothing, except that they’re Latvian, based in Riga. This is from their debut EP First Swim, which is fittingly ocean themed, intended to illustrate the chaos and brutality of the open sea. Strong first showing here. Seal Pup has generously allowed me to share the mp3 of my pick from the record below, but grab the whole thing on bandcamp or stream it all over.

Seal Pup – “Tides” (mp3)

![]()

Finally, another monster of a track from Norway’s Dr. Sepi, who I’ve posted about a couple of times now. Its title and hook may be a vague shout-out to Daft Punk, but there’s nothing French Touch about this. The track is all claws out Scandinavian mongrel carioca on PCP. Out now on bandcamp and for streaming, but Dr. Sepi has kindly provided the mp3 below for dance floor annihilation.

Dr. Sepi – “Drop it, Force it, Kill it” (mp3)

HVAD has long been among my favorite artists. Notice a Tiny Scratch for the Blue Behind is a collaboration between HVAD and Egyptian artist Abdullah Miniawy, released in 2022 on HVAD’s new label ULLLU (RIP Syg Nok).

The album is a theatrical exploration of spirituality, the failures of polytheism, and claims to offer a “telepathic experience of a valiant communist figure such as Abu Dhar Al Ghafari (the inventor of Alsalamu Alyukum).” It embraces the ancient, but intends to do so via the “transmission of new practices” and the wholesale avoidance of nostalgia. To this end, the album features Miniawy’s take on traditional desert singing, and uses a recording technique in which improvisations played on classical Indian instruments were cut directly to lacquer discs (generally used as part of the vinyl mastering process) at HVAD’s Copenhagen studio, and then manipulated as the grooves on the lacquer degraded (which they will quickly if not specifically prevented). What results is full of reverence and even warmth, but is simultaneously chillingly and urgently contemporary.

Notice a Tiny Scratch for the Blue Behind is out now on bandcamp, or for streaming. Unfortunately the limited vinyl run is long sold out.

Abdullah Miniawy & HVAD – “Meanwhile The Survivors Are Shamefully Arriving (King of Rome)” (sc)

Abdullah Miniawy & HVAD – “Notice a tiny scratch for the blue behind” (sc)